Last year I applied to Pat Tillman Scholars program. It was the last time I would apply since I am no longer eligible. It’s not the first scholarship I applied to (and certainly not the last) that I’d be rejected from. However, I think it is important to recognize that rejection happens and it happens constantly. And some – especially when intertwined with an identity can be hurtful. I have qualms about what to share and what to leverage in these applications. It often sounds like trauma porn – or a bad RuPaul episode where a queen makes herself vulnerable only to lip sync for her life and sashay away. I also have qualms about contributing to military exceptionalism – but this is a military/veteran scholarships so that moot point.

I think these were/are great essays and speak to who I am as a veteran committed to service, my research, and others. So I want to share them. They got me passed the first round so they’re somewhat successful. But what’s important is that you are and I am still successful. The essays – from my knowledge – are the same each year. So keep in mind if you’re applying again to keep your mental health in an ok place. There’s only so many times you can repeat a vulnerable memory for leverage just to sashay.

I think posting my application might be my new thing – maybe it can be called “failure porn” if that hasn’t already been done.

Discuss your motivation and decision to serve, in the military or otherwise. Explain how your unique life experience has influenced your life and your ambitions. What is the most important lesson you have learned? (400 max)

When I joined the Navy, I did not know what service meant. Like many other Americans of color, I saw the military as a way out. I saw it for the opportunities it could provide me. However, I did not realize how much harder it would be for me to reach those opportunities as a queer, Asian and Filipino American during Don’t Ask Don’t Tell.

I went to the Naval Academy Preparatory School first. There, I felt the most alone. The cadre during indoctrination suspected I was gay. They singled me out, and the harassment continued into the academic year. One day, someone even wrote faggot on my back during class. Only one person showed me kindness and helped me. That one person’s act held me together.

My true call to service came after I arrived at the Academy the next year. There, I found a cohort of queer midshipmen. For the first time I saw people like me. Working with them, I realized I could and wanted to serve in the Navy. Best of all, I knew that we had to help each other navigate the precarious waters of secrecy and advocacy. Our presence was a statement that we belonged.

They remained my anchor and only source of help during DADT, but that was not enough. In the fleet, I was sexually harassed by a sailor while deployed. Of course, I turned to those queer midshipmen for help. But what would have empowered me during that time, instead of just staying resilient and staying the course, is a leader who looked like me.

I could not be that leader. Cancer drove me out of the Navy. Still wanting to serve, I recalled those who helped me along the way. In their spirit, I went from serving the country to serving others by volunteering for other cancer patients, mentoring foster children, and helping neighbors. Service is a value that I want reflected in all aspects of my life. Today, that value is reflected in my research about veterans transitioning to college and my work advising veterans applying to college. My ambition is to continue service through scholarship, scholarship that provides veterans the tools and resources to be empowered and to empower others.

Share your academic and career goals. How will you incorporate your experiences into these goals? How will you make a positive impact? (400 max)

Pursuing a master’s degree and then a PhD in Linguistics has allowed me to raise awareness about how language mediated the adversity I experienced during Don’t Ask Don’t Tell and bring about positive change. Accordingly, my academic goal is to expose through research how discriminatory and oppressive ideologies are engrained in the language we use. My career goal is to have a platform to use my research to advocate for and to empower those of marginalized communities. Being a Tillman Scholar and hearing how Tillman Scholars talk about their experiences will enrich my scholarship and provide a network of likeminded leaders for greater positive impact.

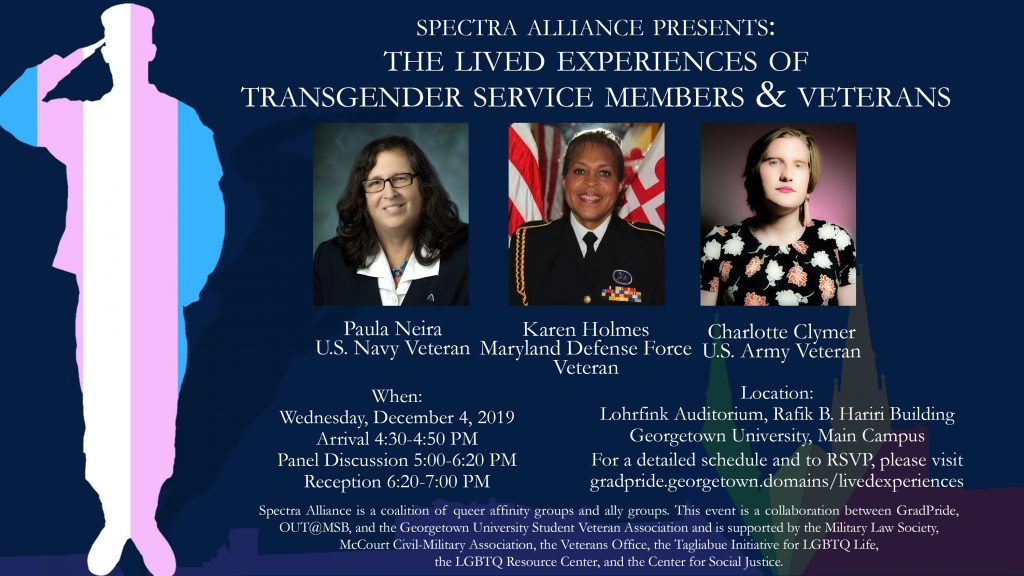

Since starting my academic journey, I have already had an impact. For example, motivated by my research on queer naval officers, I founded a coalition of queer and ally student organizations called Spectra Alliance. (Like my experience at the Academy, I knew we would be stronger together.) Our first event, which brought my research to life, provided a platform for transgender service members to share their lived experiences with our community and three other universities. Our next event is “OUT in Research,” a conference which will elevate the research and needs of queer students at Georgetown and plant the seed for a dedicated queer research program.

In 2020, I started my dissertation. I examine how veterans talk about their transition into student life. Findings from my study have already impacted veteran programming at Georgetown. For example, I initiated a community of mentors called Veterans Helping Veterans (VHV) to help other veterans transitioning to the rigors of academia. From VHV, a women-veterans special interest group emerged. And, in collaboration with the LGBTQ Resource Center, VHV will hold a queer military career panel. This panel and the veteran women’s group highlight VHV’s mission and the spirit of Georgetown: commitment to service, veterans for others, and the celebration and inclusion of diversity. It is through my commitment to service that my academic and professional goals collide. My academic goals center on developing the scholarship needed for improving those of marginalized communities. My career goals are bringing that research to life through positive social change. My research has had a positive impact in my local community already at Georgetown. As a Tillman Scholar, I can have a greater and broader positive impact in the military and in higher education.

In what unique ways has the COVID 19 pandemic affected you and your candidacy to become a Tillman Scholar? (optional, 250 words)

In 2016 I was diagnosed with Leukemia for the second time and had to receive a bone marrow transplant. While the general population has a 95-99% survival rate, I have a 68% survival rate as a transplant recipient.

While concerned about my health, my dissertation research was immediately impacted by COVID-19. My original dissertation plan was an ethnographic study of the socialization process into the US Naval Academy during the Summer of 2020. It took me two years to design the project, collect the relevant scholarship, gain access to the Academy, and raise personal funds to support the project. However, prior to meeting with the Commandant, the nationwide shutdowns took place. Two years of work disappeared.

I was still determined to start my dissertation that Fall of 2020. In July, with a new idea, I designed a new project, collected the relevant scholarship, and passed the institutional review board in two weeks. Because of my supportive faculty, I immediately began collecting data before passing my dissertation prospectus defense in November.

While COVID-19 has made doing research more difficult and canceled all my public speaking opportunities, it has elevated the inequities in marginalized communities. Examples of these inequities emerge in my own research. Now more than ever, my research can benefit from a platform like the Pat Tillman Foundation and raise awareness for positive social change in these communities.

Special Skills or Expertise (optional)

Three skills I want to bring attention to are my skills in illustration and photography, conducting and facilitating meaningful conversations, and community-building.

Before applying to the US Naval Academy, I wanted to go to art school. I had taken art classes in high school, specifically a class in graphic design where I found I like illustrating and photography. Throughout my time at the academy, I designed logos for sports teams and organized my own photography shows. While serving on my first ship, I used my photography abilities as the collateral duty public affairs officer and to document my deployments and travels. More recently, I have returned to my love of illustrating and have illustrated large murals for friends and their homes. This skill also came in handy during my graduate assistantship in the Georgetown Veterans Office where I redesigned all the flyers and information pamphlets, as well as the illustrations and logos for our newsletters, website, and online material.

A second skill I have is facilitating productive and meaningful conversations. This is because most of my research has consisted of interview data, or what we as linguists call “semi-structured conversations.” While I always have a set of questions prepared, I allow the conversation to flow on its own. And not only do I practice this skill during research projects, but I also have to later transcribe and analyze my interview data. This allows me to reflect on my own conversational mannerisms, catch things I could have asked about, and make myself a better listener. This skill has transferred to my personal life as it has overall improved how I make interpersonal connections with people.

My last skill is community-building. While in the Navy, especially overseas, I tried to connect people and help others build community with like-minded people. When a sailor needed help, I liked being able to connect them to the resources they needed. As a PhD candidate, I like to connect individuals who may share the same research interests so that they can potentially collaborate. In my department, I initiated a mentor program that matched incoming graduate students with seasoned graduate students. I also like to connect groups to create stronger communities and coalitions. I did this last year when I initiated Spectra Alliance. It started out as GradPride and OUT@MSB, two queer organizations at Georgetown and then it became five organizations.