I think the short answer-response is “sometimes” and it depends on the environment and context where one does leadership. But also, what exactly is trust? And what are values?

Rouseau et al. (1998) define trust as the “psychological state comprising the intention to accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the intentions or behavior of another” (p. 395) and can be further parsed into cognitive, affective, and behavioral bases (Mayer et al. 1995). In other words, what we think someone’s trustworthiness is, how we feel about that trust, and how we enact (do) trust.

Values are a little more abstract. Schaefer (2008) defines values as “conceptions of what is good, desirable, and proper” (p. 50) and can be categorized as personal, social, political, economic, and religious. An example of a personal value would be “loyalty” while a social value could be “equality” and “justice”. Institutions, such as branches of the military, have official “core” values. The U.S. Navy’s official core values are “honor, courage, and commitment”. The U.S. Army has seven official core values, “loyalty, duty, respect, selfless service, honor, integrity, and personal courage”. The values of an individual (or institution) can influence what norms are developed and how moral judgements are made. Jones and George (1998) argue that shared values are the primary vehicle for individuals to experience trust. Thus, when institutions instill, or socialize, individuals with specific values, they’re setting up the individuals to trust one another.

In Gillespie and Mann’s (2004) study “Transformational leadership and shared values: the building blocks of trust”, they investigated how a specific leadership style (transformational, transactional, and consultative) combined with shared values can further foster trust. To do so, they used a series of questionnaires to evaluate leadership, trust and values among participants chosen from 9 teams from a research and development (R&D) organization. The participants consisted of the team leader and two team members from each team. The results found among the leaders and members of R&D teams, the combination of shared common values, idealized influence (a dimension of transformational leadership described as “communicating and modeling important values and a shared purpose” [p. 596] ) and consultative leadership was the strongest predictor of trust.

While Gillespie and Mann (2004) elaborated on the different dimensions of leadership practices, they did not elaborate on the different value systems the participants might draw from to foster trust. It would be useful to know if the R&D organization the participants worked for had official values stated in a mission statement, if the values were specific personal values, or if the general idea of “shared values” sufficed. Thus, the study would have shed light on whether the values shared are context-bound and if so, is trust (more or less) emergent in specific contexts?

In the context of the military, I’m curious how demonstrations of “official core values” influence the maintenance of trust. Or, do individuals rely on their personal values when trusting leaders? In my master’s thesis research, one individual remarked about her arrival at the Naval Academy that she was “expected to blindly trust the firsties (first class midshipmen responsible for indoctrinating incoming “plebes” or freshmen)”. She recalled questioning the firsties as authority figures because she did not believe their (limited) experience licensed them to be “leaders”. But, she then recalled her first tour on her ship as a Division Officer and expecting her sailors to “blindly” trust her despite no experience.

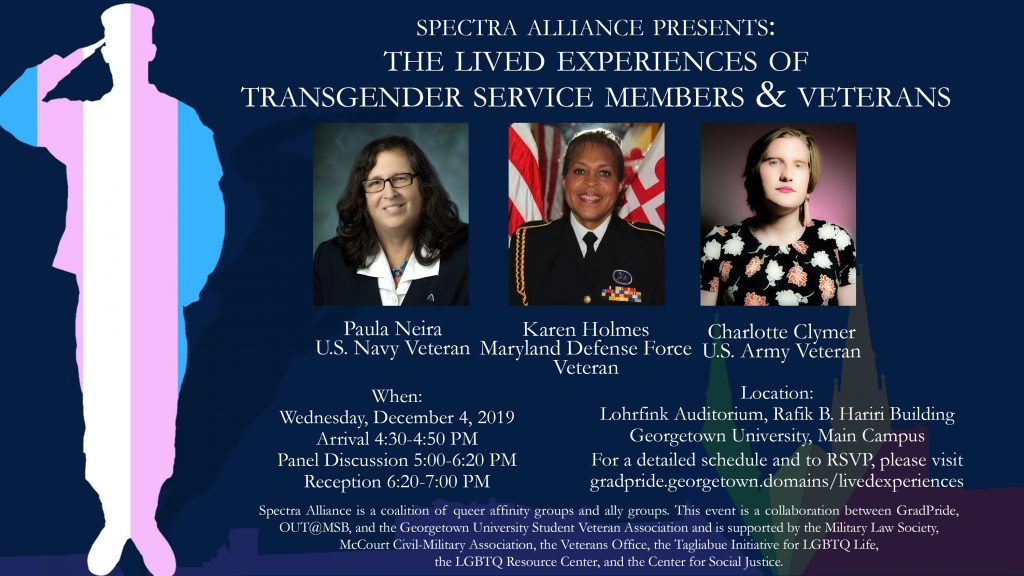

I hypothesize in institutions such as the military that other factors can override the existence of trust and shared values in order to successfully “do” leadership. In the case of my participant, when she stepped out in front of her division for the first time, her institutional authority licensed her to “do” leadership without trust, shared values, or experience. During DADT, my experience as a naval officer was leading sailors who trusted me despite their belief (which aligned with the discriminatory policy at the time) that I shouldn’t even be in the military. However, I feel as though working with these sailors, we either developed similar values or our values eventually became more aligned within the context of our duties and responsibilities. Thus, I either earned their trust through context-bound values or they simply respected my rank.

In my master’s thesis I looked at leadership style as a demonstration of power. After reading Gillespie and Mann’s (2004) work, I would be interested in expanding the study into looking at increased/decreased efficacy of leadership when considering shared values and the effects of trust.

Gillespie, Nicole and Leon Mann. (2004) Transformational leadership and shared values: the building blocks of trust. Journal of managerial psychology, 19(6), 588-607.

Jones, G., & George, J. (1998). The experience and evolution of trust: implications for cooperation and teamwork.(Special Topic Forum on Trust in and Between Organizations). Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 531–546

Mayer, R.C., Davis, J.H. and Schoorman, F.D. (1995). An integrative model of organisational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20(3) 709-34.

Rousseau, D.M., Sitkin, S.B., Burt, R.S. and Camerer, C. (1998), Not so different after all: a cross discipline view of trust (Introduction to special Topic forum), Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 393-404.

Schaefer, R. (2014). Sociology matters (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.